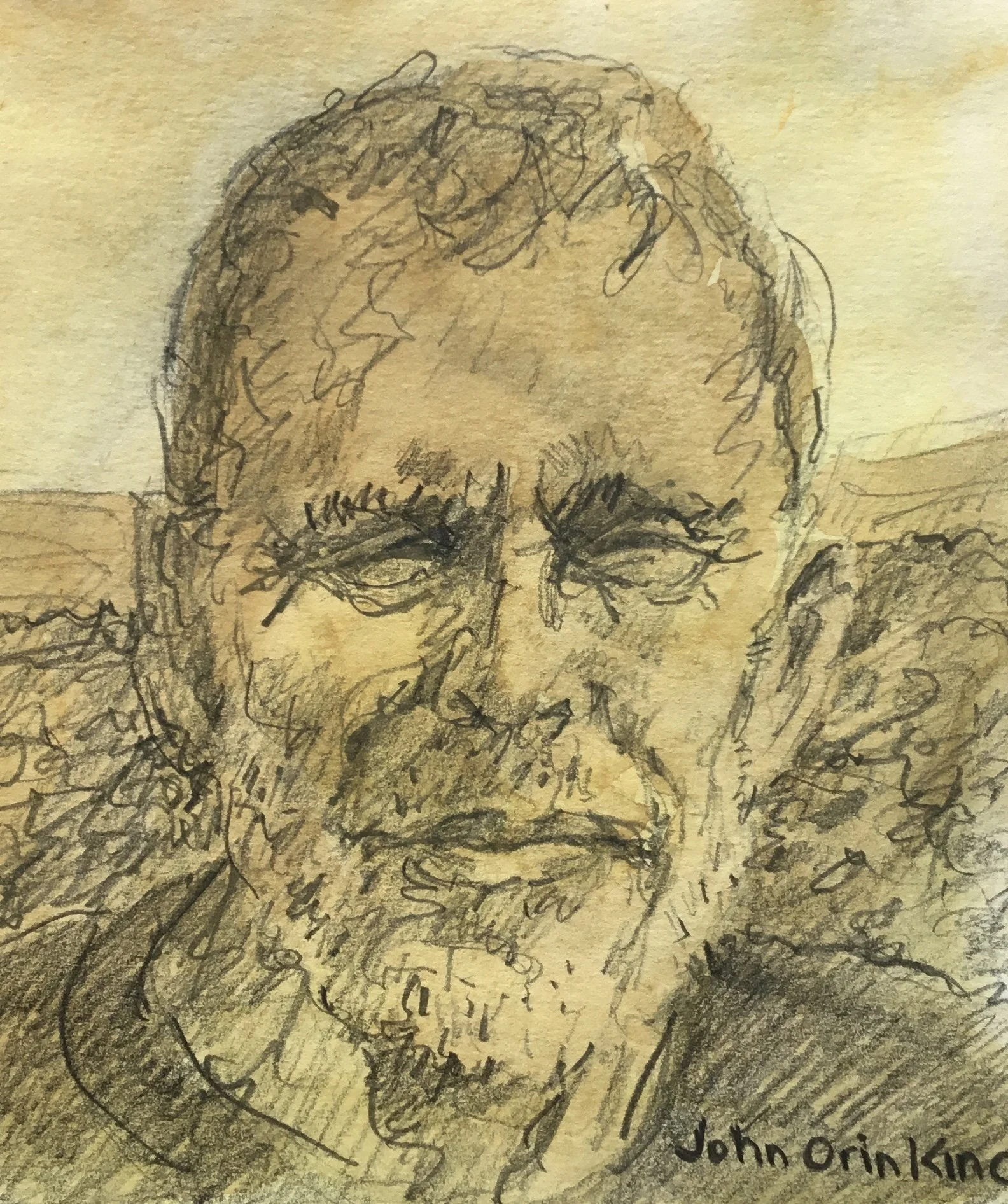

self-portrait: a portrait of oneself done by oneself (Merriam-Webster)

As an aspiring draftsman I spent hundreds of hours with pencil, charcoal or pen in hand struggling to create a convincing representation of the human face. The most available model I had was myself. Staring into the mirror I would try to see how the bridge of the nose folded into the the side wall of the nose. Looking away from the mirror I would try to represent in line on paper what I had just apprehended. Looking back again I would have to readjust my face within the mirror and look again. How exactly does the line between the upper and lower lip roll around the mouth and disappear into the face at the corners? Down to the paper and then back up again. Now the eyes. How deeply set are they under the brow? Can I twist and torture my pencil to capture the enclosing movement of the eyelid as it embraces the ball of the eye? This is intense observation, fumbling but intense. It all gets a little personal, those eyes that I am struggling to understand are looking back at me questioning, searching. It is me looking at me and not doing a particularly good job of it.

The drawing above doesn’t have a title, it depicts Place des Terreaux in Lyon France at night. Place des Terreaux is situated at the foot of the hill of la Croix-Rousse, in between the Saône and Rhône rivers. The monumental statue in the foreground is Fontaine Bartholdi. Bartholdi is the sculptor who created the Statue of Liberty. The statue depicts France, represented by the bare-breasted woman, controlling the four rivers of France, depicted by the lunging horses. The statue was originally commissioned by the city of Bordeaux. Bordeaux backed out of the commitment and Lyon took the statue; that may explain the statue and fountain’s asymmetrical placement within the square. In the background is the Hôtel de Ville de Lyon, or Lyon City Hall. In the center of the building’s facade, a half relief sculpture of Louis XIV on horseback overlooks the broad public plaza, Place des Terreaux, with Bartholdi’s magical fountain on the left perimeter mid way down the open space. A wall of classic French cafes are set back from the fountain creating the public square’s western wall. The bare breasted charioteer faces the ornate facade of Lyon’s grand art museum which runs the length of the eastern perimeter of the plaza. During the French Revolution the statue of King Louis was removed only to be replaced during the Restoration by Henri IV. Trust me, my drawing aside, standing there late at night with the sound of water flowing through and over the fountain with the mist cooling your brow and the illuminated city hall in the background is special. You are out of yourself, in another place, in another time. The description of my drawing, however, may be interesting but doesn’t say or reveal very much.

It was our first night in Lyon in early November 2018. Lyon would become Nancy and my home for the next ten months. Nancy and I were not what you would call experienced travelers. We had reached retirement, and I wanted an adventure. Nancy over a few months time warmed to idea: “Yes, let’s live in France.” Our youngest daughter was going to graduate school in Lyon, so we decided go live with her in Lyon for a year. In the morning, we arrived in Charles de Gaulle airport after a seven hour overnight flight. We maneuvered our two large bags, two carry-on bags and two overstuffed shoulder bags through the airport to catch the bullet train from Paris to Lyon’s Gare Part Dieu. What do you pack for a year abroad? I am an artist I had to bring along oil paints and brushes, right. Morgan and Vincenzo met us at the station and helped us drag our bags through the streets and trams of Lyon, dropping us of at our hotel. A few hours later they returned and gave us a nighttime walking tour of Lyon. We did not know where we we were or where we were going. Feet and legs sore, we kept our eyes on the backs of our guides, finally coming to rest in the cool mist of Bartholdi’s fountain. There we were, we didn’t speak French, we had no place to live with only a sketchy idea of how to go about living in France for the next ten to twelve months.

It was exhilarating. We were alive within beauty and an undisclosed promise.

As an illustrator you have to be consistent, with no surprises. Your client picked you for a reason: no surprises. It is challenging: the work has to be beautiful, we are selling soap, cereal, cars, vacations, whatever needs selling - no surprises. You have a system. You know the end before the beginning; you have to. Being set free from the shackles of commercial art creates its own problems; what am I trying to say, how am I getting there and the point is exactly what? For me, creating art is like a wrestling match in the best of times. The creation of the drawing of Place des Terreaux in Lyon is more like a bar fight. I had an image in my mind of where I wanted to go, but my hand and abilities had their own ideas. As I struggled with the drawing, it stared back at me. I know how to make marks; it will be fine, but it is not working. When I float the color for the night sky across the paper I have what I want. It is not what I expected, but it is the sound I was looking for

Part of gaining mastery in drawing is studying and copying the work of artists who went down the road before you, and many of them embraced self-portraiture. Rembrandt spent a lifetime in the self exploration of self-portraiture going from a brash youthful braggart to a humbled old man. Albrecht Durer presented himself as Christ-like, not the suffering servant-redeemer type of Christ. Frida Kahlo’s eyes stare out at you from under bold dark eyebrows as if to say, “Do you have a problem?” The self- portrait is now an opportunity to project a vision of yourself in the world.

In my self-portrait, I am sixty-four years old, standing in front of a field of sun scorched sunflowers. The location is the Maseta (plateau) of northern Spain. My friend Ed and I are walking the Camino de Santiago pilgrimage. We have been walking for twelve days starting in the French Pyrenees. This specific route of the Camino (the way) is the Camino Frances. We started the day walking in the dark before sunrise to beat the midday sun’s heat. The sun is at its peak. We have walked fourteen miles and are approaching a town. The sun has scorched the sky, the sun flower fields and my head.

I had been declaring my desire to walk the Camino for two years and got within a week of just flying off to France and Spain and starting my walk. But then my daughter Morgan asked if she could join me after she finished her studies in France. How could I refuse the offer? Circumstances would ultimately preclude Morgan from doing the Camino. It was important; I needed to do it, but it seemed to be slipping away. One of the motivations for moving to France was positioning for the Camino. Thirteen weeks before the drawing of me in the sun I was being operated on in Lyon. The abdomen muscles on my lower left side were being sliced through to repair a hernia. Supposedly I would be good to go in eight weeks. My surgeon cautioned me to take it slow across Spain. The first week of walking I could feel the plastic mesh inserted into me being pulled as I exerted myself. My purpose in the Camino was spiritual and personal. My expectation was one of renewal and direction. Instead, I came to an immediate realization of my life’s vanity. It was physically and emotionally crushing. At the time of my self-portrait in front of the flowers, I was on the other side of that personal journey. There were many more miles ahead of me on the Camino full of drama and laughter, but at that moment I could have ended my pilgrimage satisfied.

As you progress in your art you become aware that when you do a drawing or a painting of an individual or group of individuals, that somehow no matter the actual physical characteristics the people possess, something behind their images looks like you, even when you faithfully render said characteristics. It can be hard to put your finger on. You have spent a lifetime looking at yourself, your family and your friends. The way you move and interact socially all gets in there. It is the ground from which you create.

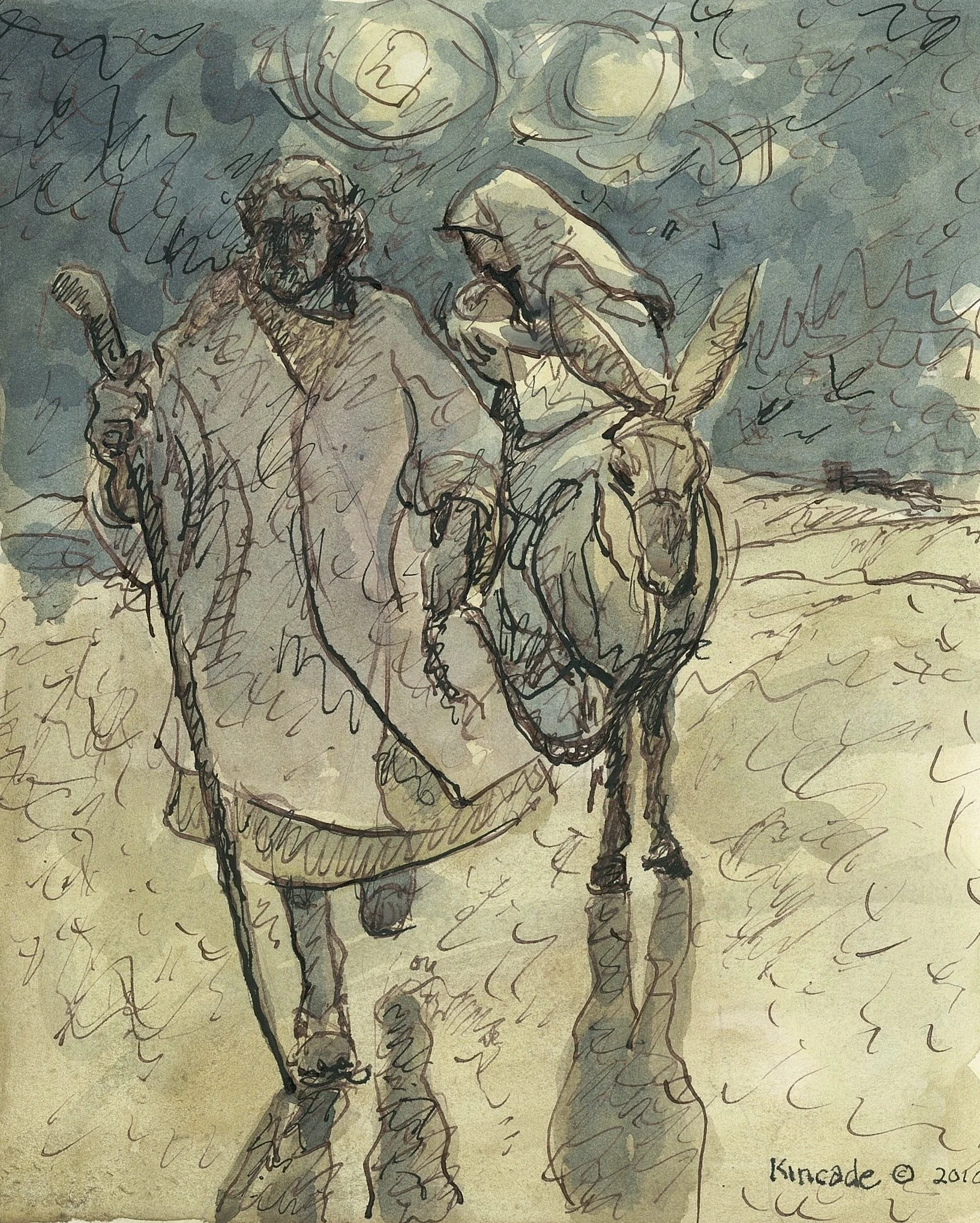

This drawing is our family Christmas card from 2010. The card depicts The Flight Into Egypt. Since Having been warned in a dream that King Herod was intent on killing the baby, he flees with Mary and the baby to Egypt. Our family tradition of creating Christmas cards started with my father.

My father was a freelance illustrator. In the 1960s and 70s, as many illustrators did, he would create and send out Christmas cards to friends, publishers, agents, art directors and fellow artists. Dozens of unique Christmas cards from his artist friends decorated our house, adding spice to our holiday. But, in the mid-seventies a disease devastated my father’s nervous system. No more cards were created. Some years later I and my young family moved in with my parents to help care for my ailing father. The time spent with him was a gift. We got to know one another as men, not just father and son. Many years after his death, I created our first family Christmas card. It is a deconstructed version of one of his cards. It was an intentional reflection on our conversations on life, art and the choices involved. I could place his card along mine for comparison, but as far as I am concerned that would illuminate nothing. My intentions seem to fall away from me now.